ZURICH, Switzerland – Tension at the Movenpick Hotel on July 4, 1988, could not have gotten much thicker.

The delegations of the U.S., Brazilian and Moroccan federations were anxious and eager to discover whether they would be selected to host the 1994 FIFA World Cup.

Originally, decision day was set for June 30, but on March 3, FIFA changed it to July 4 – Independence Day in the United States -- making some soccer observers feel the USA was a shoo-in.

The U.S. was hardly that. While its bid was solid, there were concerns. There was a question of whether grass could be placed over the artificial turf football fields. There was no strong, national pro league. The country simply hadn’t shown itself as a hotbed for the game.

There also was the question if the U.S. Soccer Federation could find a television network or networks to originate a strong signal for not only the games in the states but for the rest of the world.

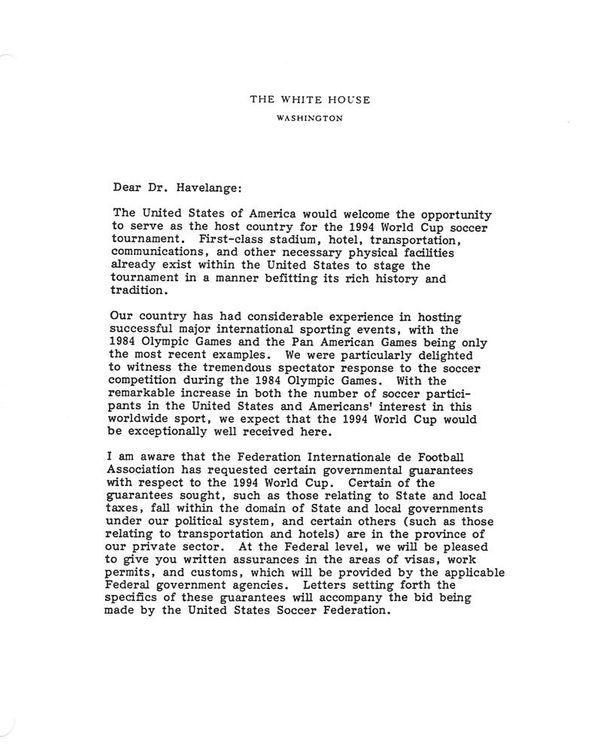

The last part of the journey began on Sept. 30, 1987, when FIFA headquarters in Zurich, Switzerland received a personal special delivery from three gentlemen representing the United States Soccer Federation. Their package, on the surface, looked like a couple of huge phone books.

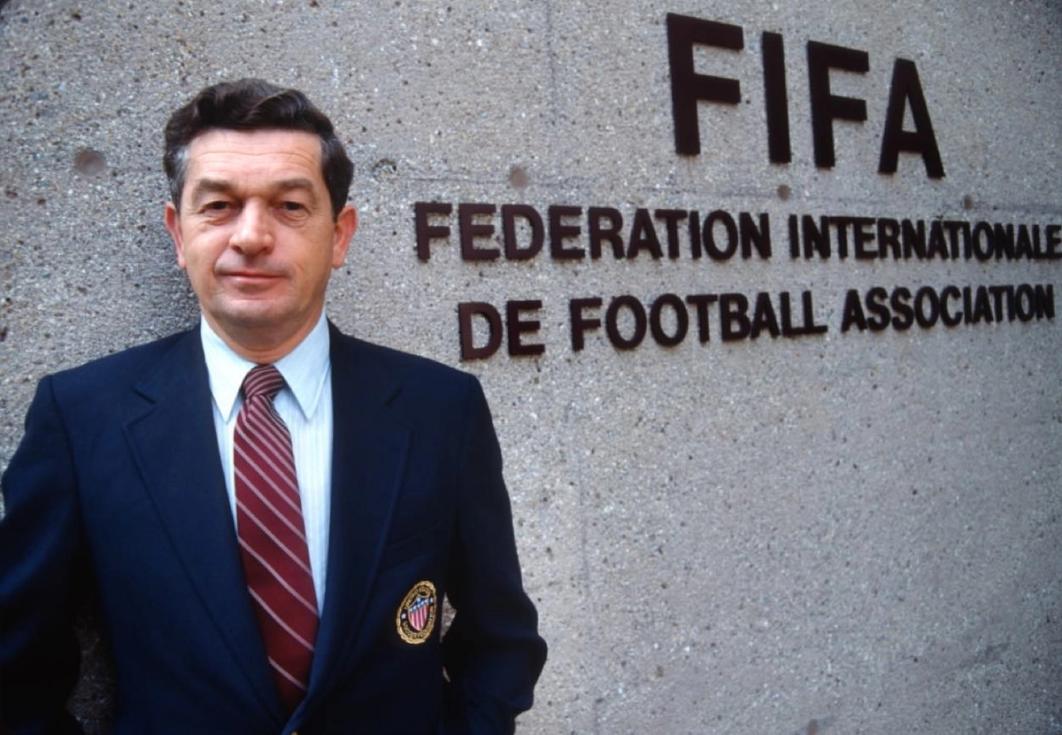

The material in those "phone books" would go a long way towards determining whether the United States would receive the go-ahead to host the 1994 FIFA World Cup. Federation officials, including President Werner Fricker, were optimistic the 381-page document would.

At a press gathering in New York City, Fricker said he felt the U.S.'s chances were "excellent" after the Federation spent $500,000 on the bid up until then. The USSF had learned well its lesson from its hurried 1983 bid to host the 1986 World Cup after Colombia dropped out; Mexico was selected as host. For the 1994 bid, nothing was left unturned. All of the I’s were dotted and the t’s crossed.

This is a timeline of how the final bidding process and the FIFA Executive Committee’s decision transpired at the Movenpick Hotel:

9 a.m. -- The FIFA Executive Committee began its session in the Regulus Room. The committee held a draw to determine the order of the final presentations. Three plastic eggshells were placed in an oversized brandy sifter. The order: Brazil, Morocco and the United States.

The committee also outlined the procedure it would follow through the next four hours. "We struck fairly rigidly to it," says FIFA senior vice president Harry Cavan, who chaired the meeting. FIFA president Dr. Joao Havelange, a Brazilian, did not chair the meeting or vote so there would be no conflict of interest.

The committee received a report from the technical committee and took a break to read it.

10 a.m. -- The Brazilian delegation, including Brazilian Football Confederation President Octavio Pinto Guimares and confederation administrator Moacir Peralta, gave its presentation. Each delegation was limited to 30 minutes.

Cavan later said, "We had quite a bit of emotion collectively from all three, least of all from the United States."

The U.S. delegation, Cavan added, was "very level voiced, very quietly put and very effectively put."

10:40 a.m. -- The Moroccan delegation, including minister of sport Abdellatif Semlali, met with the committee.

Semlali said he urged FIFA to continue helping the development of soccer in Third World countries. "I tried to prove that the United States does not need such competitions," he said. "They have so many already."

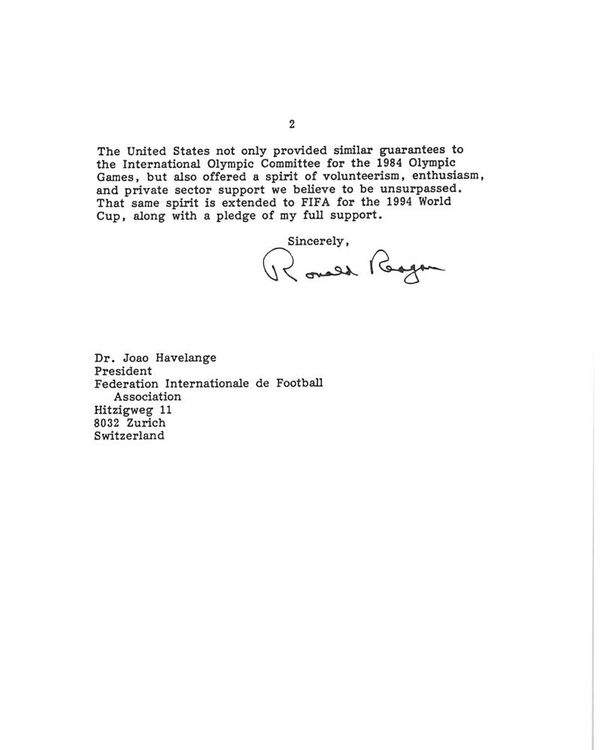

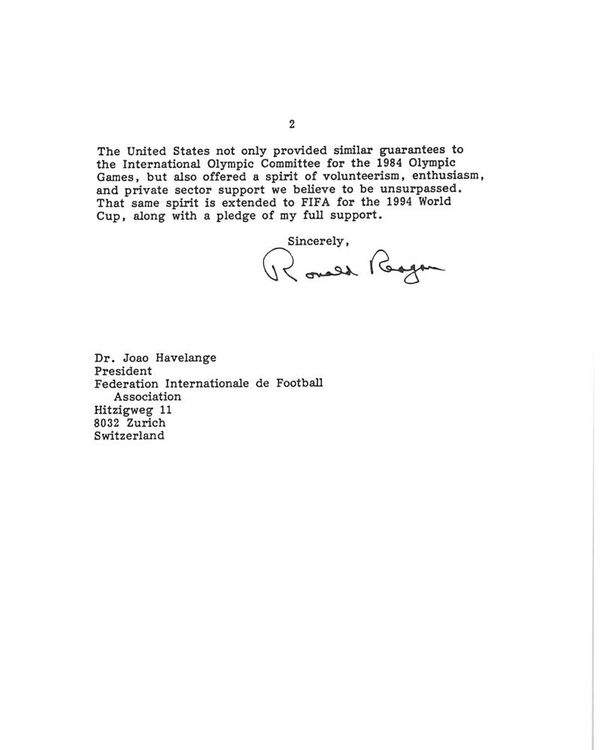

11:25 a.m. -- The U.S. delegation was called in and gave a 22-minute presentation, including a two-minute speech on video tape by President Ronald Reagan.

The five men who met with the Executive Committee included U.S. Soccer President Werner Fricker, World Cup USA 1994 director Paul Stiehl, former U.S. Soccer President Gene Edwards, World Cup USA 1994 counsel Scott LeTellier and Rey Post of Eddie Mahe Jr. and Associates.

"It was exactly, give or take a minute, how long we thought the presentation would be," Stiehl said. "We didn't want to make it so long that it would have bored everybody to death. At the same time, we couldn't cut it too short.

"We were all very satisfied. I think we were able to optimistically read some of the faces."

1:05 p.m. -- The three heads of the delegations, including Fricker, were called into the Executive Committee meeting, and they are told the news. Fricker, showing no emotion, walked back to the U.S. waiting room, where he slammed the door. "He's stone-faced," Stiehl said. "He's very good at that."

Once inside the room, Fricker put his right thumb up to signify victory. One observer later said that Fricker had such a sour look on his face, it was as though FIFA told him not only won't the U.S. host this World Cup, it never will stage one at all.

Several minutes later, the Brazilian and Moroccan delegations walked over to the U.S. room to congratulate the Americans.

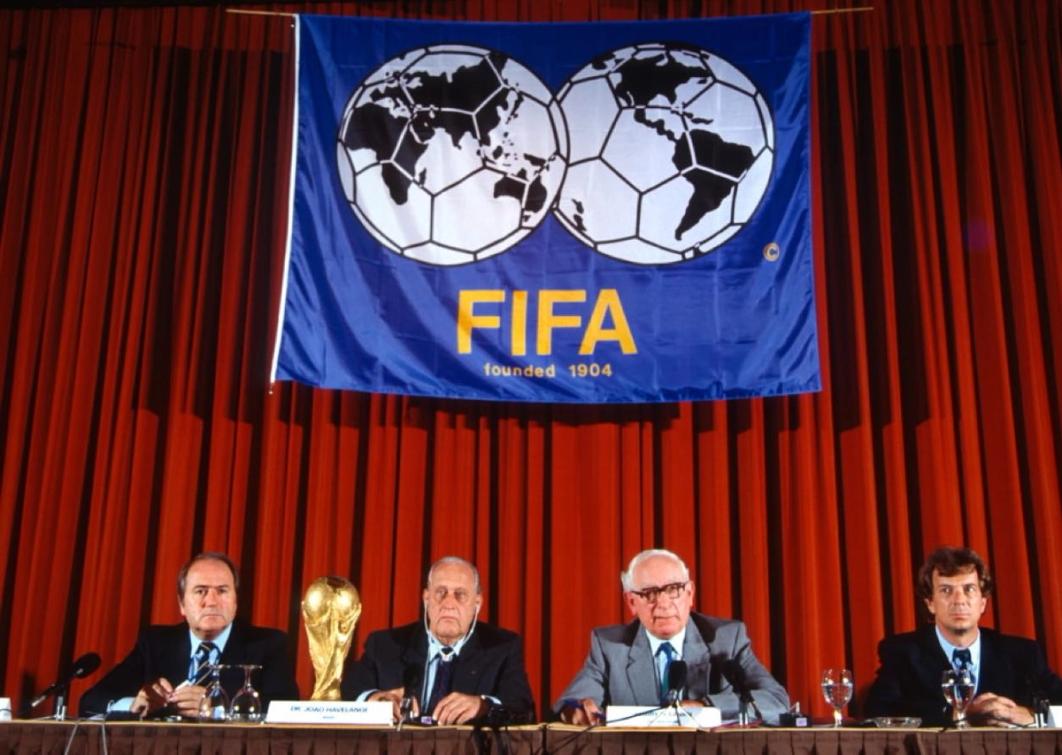

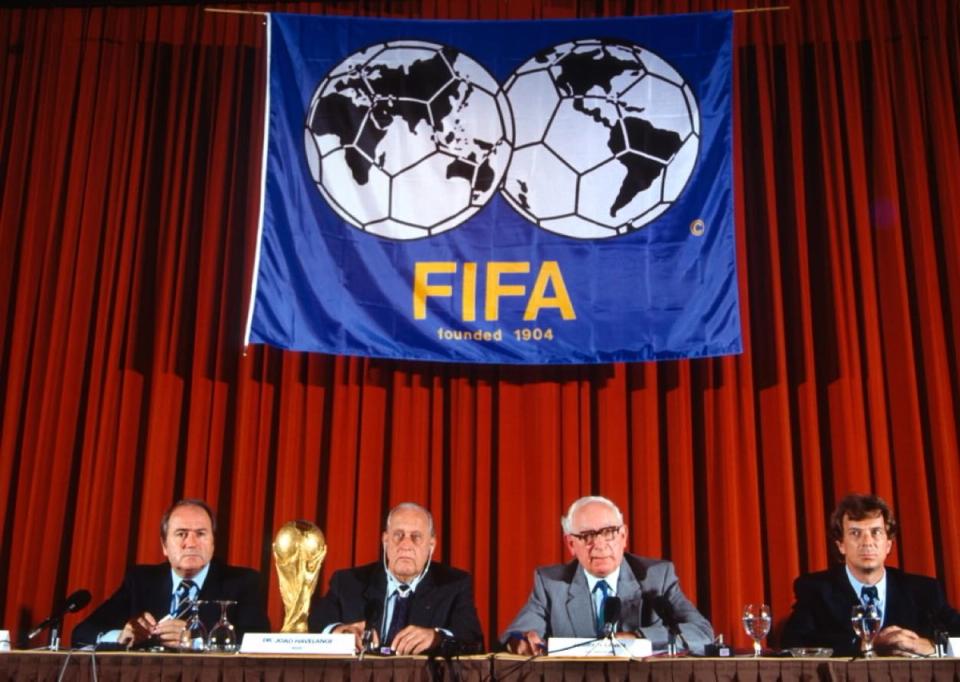

1:21 p.m. -- Before about 100 members of the international media, Havelange let Cavan make the big announcement.

"After very careful and very responsible consideration of all the information that has been brought to us today," Cavan said, "the executive committee of FIFA has, in a very democratic way, arrived at a conclusion that I am happy to announce on behalf of the President of FIFA, the Executive Committee of FIFA, the following results.

"It was a card vote, a secret vote. It resulted as follows: Brazil two, Morocco seven, the United States 10.”

There were cheers from the audience.

Cavan continued, "I declare on behalf of FIFA that the host country for the 1994 World Cup will be the United States of America."

Cavan, who chaired the Executive Committee meeting, tried to measure the World Cup's impact on soccer in the U.S. "I think obviously it will have a tremendous development exercise on United States football," he said.

In fact, progress already might have taken place. "I noticed this morning, if I am allowed to repeat something, I noticed the delegation of the United States used the word football," he said. "I was quite happy about that because I have for years been trying to get them to do it."

Stiehl thought the announcement "was a little anti-climactic."

"I felt very comfortable from the time we handed in the bid last September," he added. "I had time to review our bid and I thought, 'How could anyone rationally not select us?'

"My only concern was we still had time to screw it up."

A little later, Fricker met with the U.S. media and shared his emotions.

"Obviously, the first instant reaction is relief," he said. "The decision is made. After that, I guess the next thing is, 'What's next?' "

Fricker certainly understood the task at hand. "We now have the timetable set for us. We do not have the privilege to say, 'We'll do it someday.' We must do it now,' " he said.

The total cost to produce the bid, beyond the two “phone books”, reportedly was in the neighborhood of $1.4 million, given FIFA's follow-up requests for material and other expenses.

"When they said we had it, I knew our sport was reborn," said Jim Trecker, press officer for World Cup USA 1994, "and I knew our country was in for a treat beyond anyone's wildest dreams."

Hours later, several members of the U.S. delegation gathered together in the lobby of the Zurich Hilton. Champagne was passed around, and Fricker lifted his glass in a toast.

"It was very nice to work with a wonderful group of people and thanks for all your support from the people back home," he said.

As big an accomplishment as securing the right to host the 1994 FIFA World Cup was, the real hard work was just only beginning.

Six years later, the United States hosted a World Cup where 3.5 million people (69,174 per match) watched in person. Despite being the last 24-team FIFA World Cup, the mark remains the tournament’s attendance record to this day, and one that will likely be shattered when the competition returns to North America in 2026.