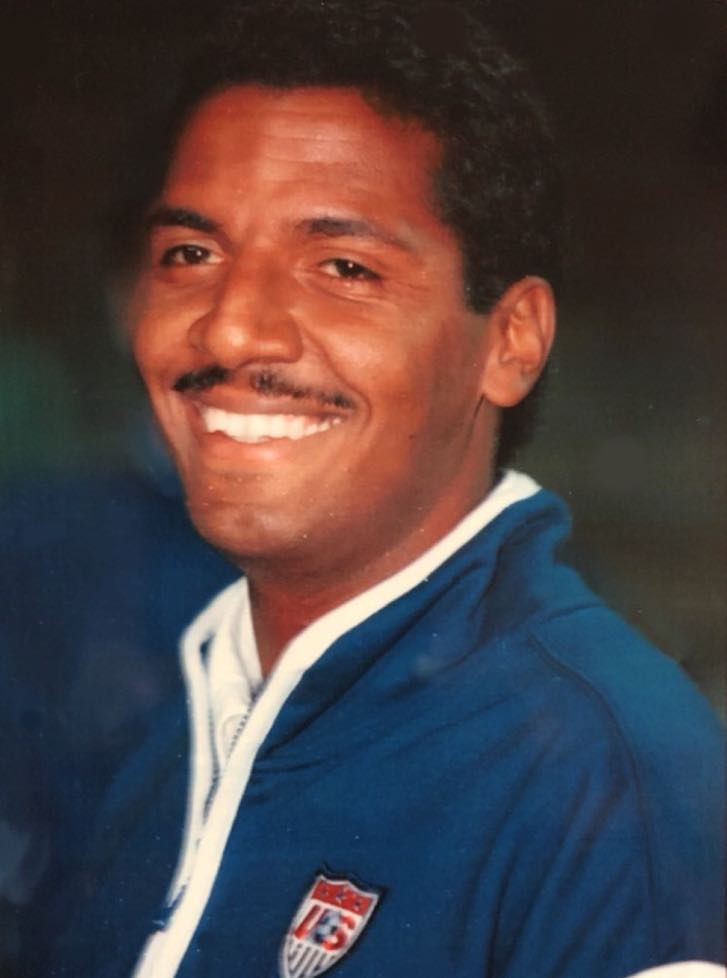

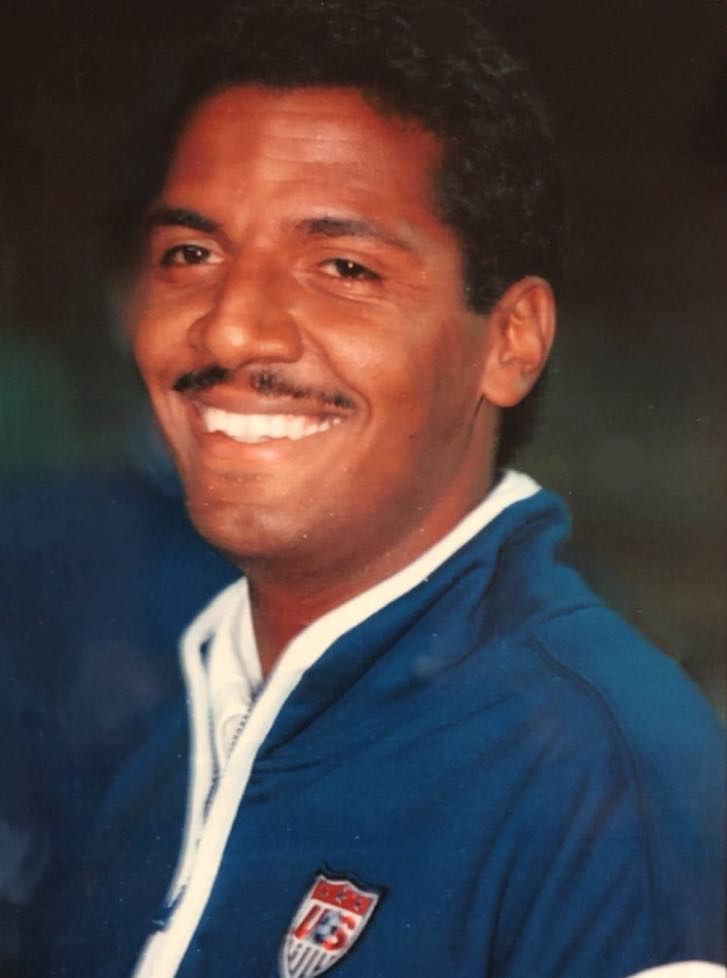

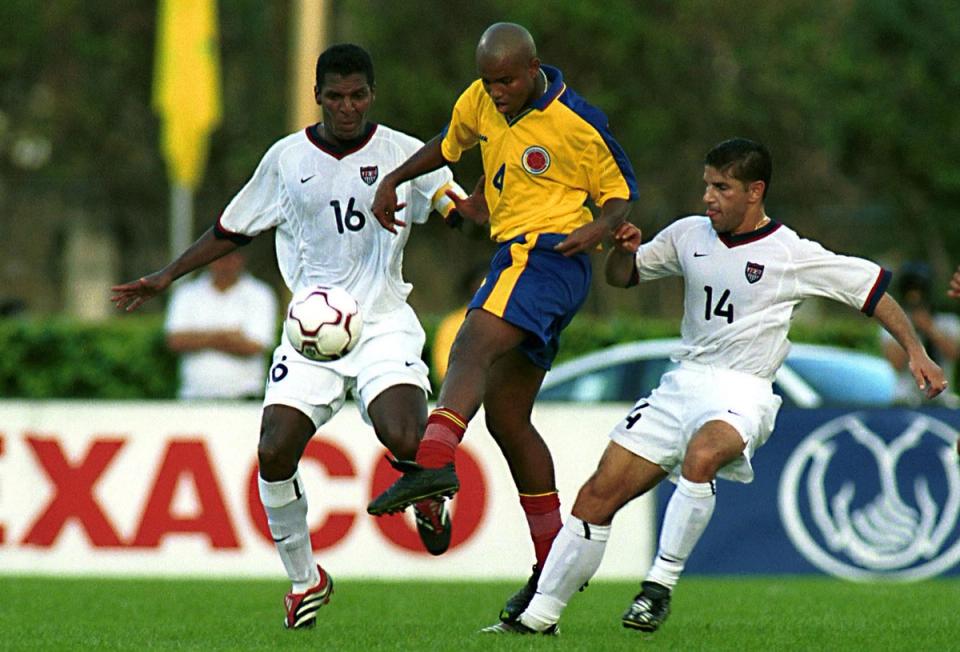

HISPANIC HEROES: Carlos Llamosa Rediscovered Soccer Dream in U.S., Represented USMNT in 2002 World Cup

How the Colombian-born defender went from Janitor at the World Trade Center to D.C. United and on to the 2002 U.S. World Cup Team

In 1986, club officials offered him a contract. He brought up the school issue and the team said it would be flexible. "Back then all the games were on the weekend, so I didn't have any conflicts playing a midweek game," he said. "That was special for me."

So was getting an education. Llamosa considered pursuing a college degree because he realized how fleeting a professional career could be.

"I always had it clear. Colombia is a Third World country," he said. "Too many kids coming from lower income neighborhoods look at a soccer career as a way out. But if that is not accomplished then you need a Plan B. Any of those soccer players, they didn't have any education to succeed in life."

Llamosa gave credit to his parents for instilling that in him. He remembered their words: "You've got to go to school. After school then you can go and do college. We support you in your soccer career. Just in case something happens, you have a Plan B for your life."

"They wanted the best for me." he added.

In 1991, Plan A worked for Llamosa, who was loaned to first division Atlético Huila.

Several brothers and sisters had emigrated to the U.S. and Llamosa's mother obtained a green card for him. He had no plans of moving but wanted to use the card to visit his siblings in New York.

Llamosa then encountered problems with Colmena.

"The team who owned your rights, they basically owned your rights … even if that team disappeared," he said.

He had excelled at Huila, which wanted to purchase his contract. "They treated me well. They paid me well," Llamosa said.

Negotiations fell through when Colmena asked for too much money. The loan expired. Colmena said it would find another team, but it never did.

"I got my green card and I had four months to travel to the United States or otherwise I'm going to lose the green card," he said. "One month, two months, three months and he [the owner] never found a team. I decided to move to the U.S."

That meant making the difficult decision to give up soccer. He decided to attend college. In 1991, the professional soccer landscape in the U.S. was barren - seven years after the North American Soccer League went belly-up and five years before Major League Soccer kicked off.

"That was a sad moment and decision," Llamosa said. "For me to make that decision to move to the U.S. was basically saying goodbye to soccer. That was something that had to be done.”

While Llamosa received partial scholarship offers from Southern Connecticut State (with the help of former Mexico national coach Juan Carlos Osorio) and had strong interest from Long Island University (with the help of head coach Arnie Ramirez), it wasn't enough to pay the entire way.

So, Llamosa went to Plan C: make enough money to attend college. He worked as a janitor at the World Trade Center. In fact, he employed there on Feb. 26, 1993, a day that ended in tragedy.

On Fridays, workers received their paychecks and got an extra half hour at lunch to go to the bank. Llamosa made a life-changing decision to eat lunch in a Chinese restaurant with his co-workers. No one has to remind Llamosa that he is lucky to be alive because during that window, the building and his basement office were bombed by terrorists.

Llamosa said he was "very fortunate, grateful with God."

"A lot of people in the building, around the building were on the same page," he said. "That's why there weren't too many casualties that day."

Though he toiled in Manhattan during the week, Llamosa played in semi-pro leagues in Flushing Meadow Corona Park in Queens on Sundays.

Legendary El Diario journalist Pepe Pertuz was impressed and suggested Llamosa try out for an A-League expansion team called the New York Centaurs, which played its home games at decrepit Downing Stadium on Randall's Island. Despite a side that boasted USMNT defender Janusz Michallik and future MLS players Dan Calichman (LA Galaxy), David Vaudreuil (D.C. United) and goalkeepers Jim St. Andre and Bo Oshoniyi, it underachieved with a last-place finish (6-24).

Llamosa's talents did not go unnoticed by Steve Sampson, who coached the U.S. squad at the 1998 FIFA World Cup, and United coach Bruce Arena, who became USMNT coach later that year.

The 5-11. 166-lb. defender already had applied for U.S. citizenship. Had the stars aligned and his paperwork not been delayed by governmental red tape and incompetence, Llamosa might have been a member of the France '98 squad. In March 1998, Sampson asked Llamosa if he wanted to play for the United States. Llamosa’s citizenship papers needed to be rushed because Sampson wanted to see how he fit into the squad by the final warm-up game against Kuwait on May 24.

Llamosa got a world-class run-around by the U.S. government. He missed United training to fly up to an Immigration and Naturalization Office in New York City. MLS, based in Los Angeles at the time, had a lawyer advising Llamosa. At 8 a.m., he was told he needed to talk to his attorney, but it was 5 a.m. in LA.

"That was a waste of time because everything was far away from each other," Llamosa said. "They said, 'Since you live in Virginia, your file must be in Virginia.' I went to a federal building there. 'No, your file is not here. It must be in New York.' I said, 'I went to New York to Federal Plaza in Manhattan. 'No, it’s the Federal Plaza on Long Island.' Time started going, going, going. I was so anxious. I was thinking that this was my only chance to play for the National Team and have an opportunity compete in a World Cup. The Kuwait game came. No citizenship, no World Cup."

Llamosa was advised by an INS official to restart the process with a new picture, fingerprints and paperwork.

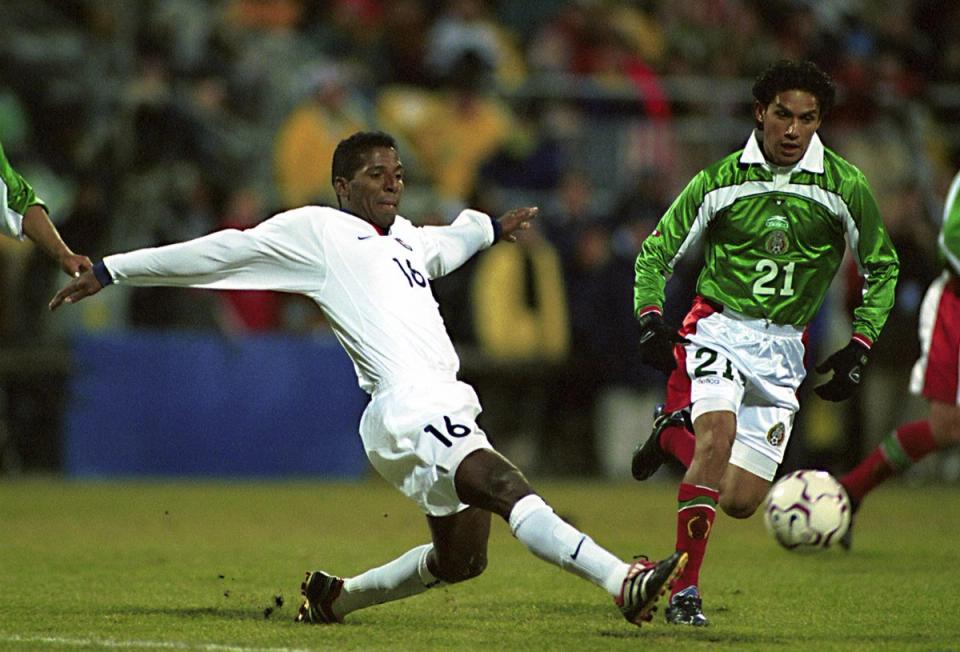

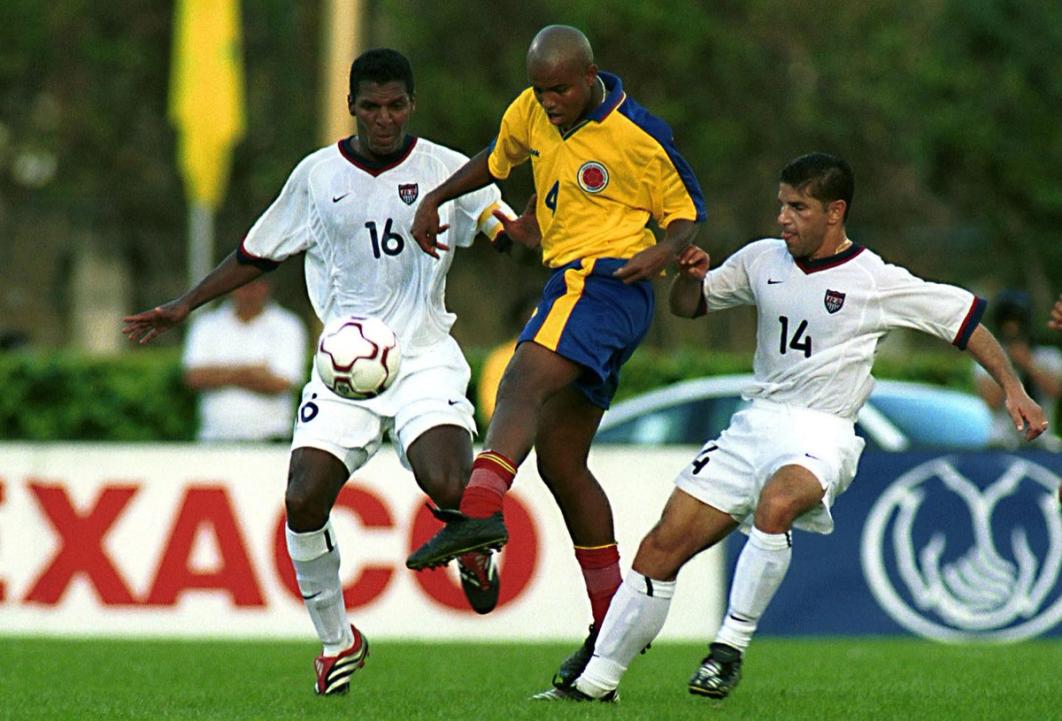

Only 14 days after becoming a citizen, Llamosa made his USMNT debut at the "ancient" age of 29, in Arena's first game as coach. He lined up alongside D.C. teammates Pope and Agoos in an international friendly against Australia in San Jose, Calif. on Nov. 6, 1998.

“In that game I took a bullet for the team. I got a red card."