STEVE SWANSON, who coached her on youth national teams and at the University of Virginia, loves the flute story, relishes it – because, of course, Becky is the quintessential team player, the one who will do anything for her team, the one without the ego.

Her mother remembers a game where five-year-old Becky felt she let her team down. Becky was serving her rotation at goalkeeper; the ball went between her legs, and the other team scored. She did not take it well. She sat in the back of the Green Ford Star mini-van and wouldn’t come out.

Becky and her mom walking out of the tunnel at the USA-Ireland Send-Off Series game at Avaya Stadium on Mother's Day

“She just sat there by herself in the garage,” says Becky’s mother. “She has always been super hard on herself. We call it ‘Becky vocabulary.’ – If she says she has a rotten game, we know she probably played pretty well. If she says she had an okay game, we know she must have been great.”

Swanson also notes Becky’s tendency to be hard on herself.

“I first met her in the under-16 camp. In my mind, Becky was one of the top players. When we talked with her at the end of the camp and asked her how she thought it went, she put herself all the way down at the bottom. She’s very critical of herself – and that aspect of her personality has been a catalyst for getting her where she wants to go.”

Like many of the USWNT, Becky was a fanatical trainer: “I’d kick it up on a slanted roof and then wait for it to come down, and I’d do that for hours after school and the perfectionist in me would have to do twenty in a row perfectly. Or I would dribble around lawn chairs and I would have to do it in one touch, and it would have to be twenty that were absolute perfection or I wouldn’t allow myself to go inside.”

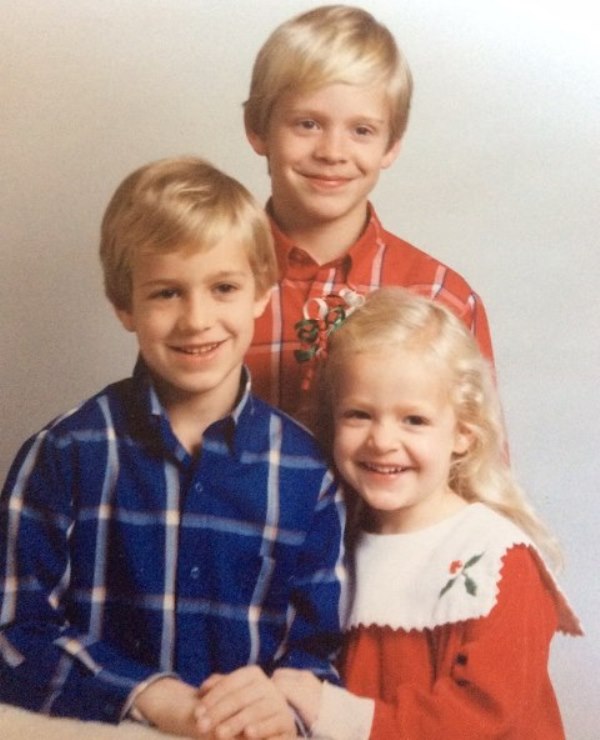

Beyond being driven, she was also tough – due largely in part to her role as her older brothers’ “guinea pig.” They’d duct-tape plywood to her arms and take slap shots at her; they’d see how far they could launch her off the couch; they’d roll her into a blanket like a burrito – so tightly that to this day, she does not like being tucked in; they’d steal her stuffed animals and beat them up while she tried to rescue them.

Becky and her brothers, Grant and Adam, during their childhood

Once, they accidentally hit her in the face with a bat – she was gushing blood but her brothers didn’t want to get in trouble so they slapped a bandage on her and tried to barricade her upstairs; she escaped and her parents took her to the hospital where she got stitches.

“Aside from physically toughening me up, they made me mentally stronger,” says Sauerbrunn. If she cried, they’d call her a baby. If she said ow a little too loudly, hoping that her mom and dad would hear, they’d hit her harder, having caught onto her tactics. “I learned how to take it. It taught me how to not really rely on other people to solve my problems. I think that kinda stayed with me.”

Her tolerance for pain came in handy during her first national team cap against Canada. In the second half, Sauerbrunn went up for a challenge in the air and the Canadian player attempting to flick the ball instead flicked Becky’s face.

“And I’m trying to shake it off– then I went to feel my face and my nose was like all the way over here. But I was like, okay, well, I can try to keep playing.”

Blood was “gooshing” down her face and when a nearby teammate caught sight of her, she looked at her with horror and told her to get off the field. Sauerbrunn headed to the sideline, holding her nose with her shirt – and when she pulled her shirt away, the coach flinched and muttered, “Oh my God.” The team doctor reset the nose right there in the locker room. Becky played in the next game with a “McGyver-like mask” made out of random materials they happened to have on hand in the training room – a contraption with the same industrious, ramshackle style as the plywood-hockey ensembles her brother would fashion for her as a kid.

Despite using her as their "guinea pig", Grant and Adam also taught Becky how to read and instilled in her a love for books from a young age.

Her brothers weren’t just brutes – they also taught her how to read. “I had trouble when I first started out and my brothers would read to me and help me figure out the words,” says Sauerbrunn. The Sauerbrunns were a family of readers – her parents collect rare books, antiquities, and children’s books; the living room is lined wall to wall with bookshelves and the three Sauerbrunn kids grew up loving to read.

Once, when she was 10 or 11, a coach told Becky she needed to learn how to read the game. “Becky asked me, ‘Mom, what does it mean to read the game?’ And I said, ‘It’s like with a book – you’re predicting what the characters will do, guessing a few steps ahead, figuring everything out.’”

As a center-back for the U.S. Women’s National Team, who intuits how each play will unfold and where she needs to be, she is very much a reader of the game now. She is the only member of the team to have played in every match and almost every minute in 2015.

And her mother’s desire to have well-rounded kids has panned out.

Becky and USWNT teammates exploring Mexico on their time off

“Becky is cerebral. She’s always reading, she writes very well, she thinks. She’s not just a soccer player,” says Swanson. “If she goes to China for a tournament, she wants to go see the Great Wall. If she goes to Arizona, she wants to go see the Grand Canyon. She’s an explorer who wants to learn.”

Now, living in Kansas City, her father reports that Becky has even asked for him to mail her the infamous flute.

Gwendolyn Oxenham is the author of Finding the Game: Three Years, Twenty-Five Countries and the Search for Pickup Soccer and the co-director of Pelada.