From Lusitanos to Pioneers: An Old Mill Town’s Enduring Passion

The Ludlow-based Western Mass Pioneers return for the 2022 Open Cup, carrying on a tradition begun a hundred years ago in the small Massachusetts town by the Gremio Lusitano Club.

It's almost spring and, as the weather warms and the days grow longer, young players begin to arrive at the Lusitano Stadium. It’s a tradition that stretches 100 years into the past.

A statue of Mozambique-born Eusebio da Silva Ferreira – the Black Pearl of Portuguese soccer fame who was known the world over as, simply, Eusebio – greets visitors at the stadium’s front gate. On the right is a barn-like concession area, also housing the Gremio Lusitano Wall of Fame with trophies reaching to the ceiling.

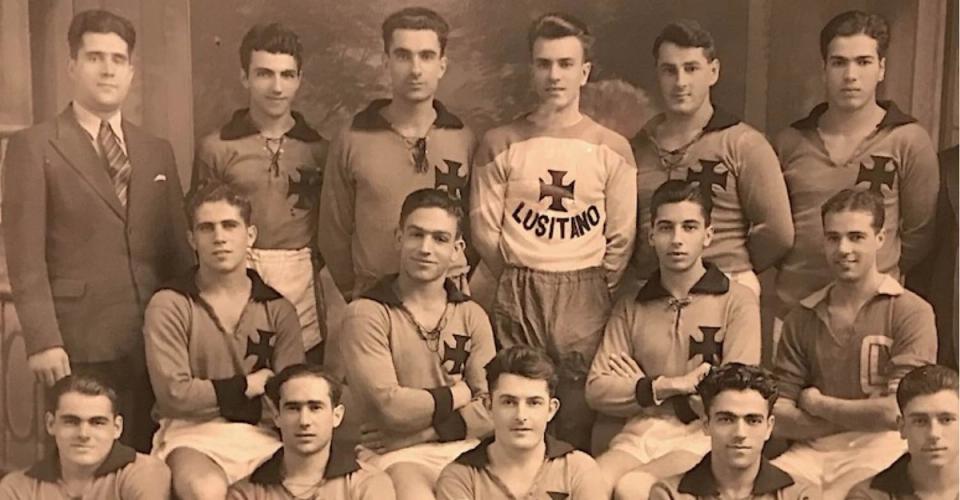

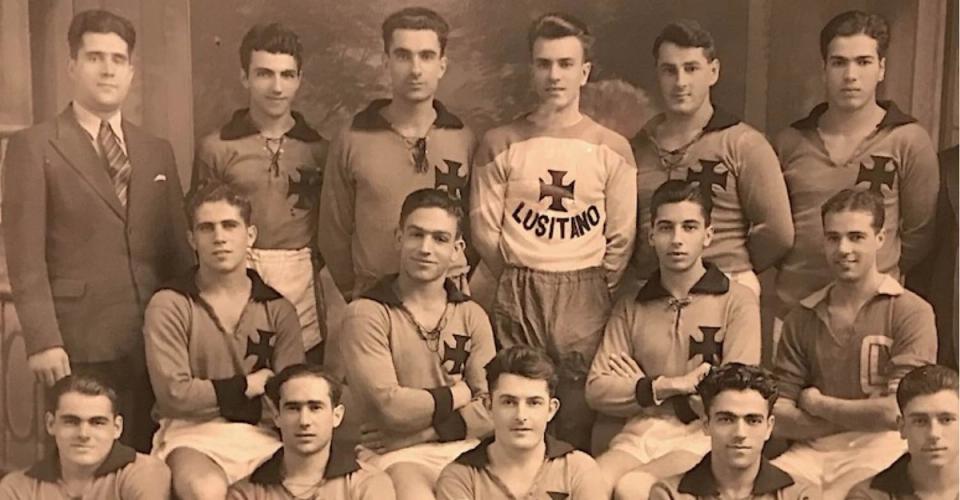

Soccer players have been coming here since 1922, when members of Gremio Lusitano, a culture and recreation club, lined out a dirt field on Winsor Street, across from the clubhouse. The club team competed against opposition from other New England mill towns. Soon, Gremio Lusitano FC was developing players for the U.S. National Team, advancing deep in both the U.S. Amateur Cup and National Challenge Cup, as the U.S. Open Cup used to be known (they are four-time Quarterfinalists), and contending in the revamped American Soccer League (ASL).

In the 1940s and ‘50s, the stadium – then called Franklin Field, likely after its proximity to nearby Franklin Street – attracted capacity crowds for matches, including several against top European teams like Everton FC. A crowd of 4,500 watched on when Lusitano played to a 3-3 draw with Jönköping FC of Sweden in 1951. At the time, Ludlow’s population was listed at just more than 8,000.

By the ‘60s, the jute mills had closed and soccer’s popularity faded nationally. But Lusitano held its traditions tight. For a while, the field was retrofit for baseball, though soccer remained the club’s primary activity.

Ludlow has long been isolated, both culturally and geographically. The country’s soccer booms and busts have had little effect here. “Parents and grandparents grew up in that soccer world, so as you raise your kids, it’s toward soccer,” said former Lusitano player and current general manager Greg Koloziey, who also coaches the local high school team. “We have a lot of hard-working coaches, kids start at a young age.”

Gremio Lusitano FC favored a style of play familiar to Portuguese people everywhere, heavy on skill and tactics. And the immigrants’ sporting prowess translated to interscholastic play, Ludlow High School winning 17 State soccer titles.

“It was in the culture, the way we played and it goes back to our heritage,” club historian Joao Bernardo told usopencup.com. “Nundy Batista and those guys were some of the best athletes around. They played basketball, football – the two years they played football were the only two years Ludlow [High School] won in football. But the soccer team lost, so they said ‘you guys are not playing football no more’ – that’s not our game. And they brought the guys back. At the high school level, you see these great players dribbling the ball, passing the ball around. That’s why there’s all these championships.”

Lusitano Stadium is a center of activity in an area that feels like a slice of Portugal. From the early 1900s, several Massachusetts mill towns developed similar setups, the most successful in Fall River, symbolized by the 15,000-capacity Mark’s Stadium. The Portuguese clubs remain active but many playing fields have been abandoned.

After the American Soccer League (ASL) folded its New England division in the 1950s, Gremio Lusitano played in local competitions such as the Massachusetts & New Hampshire State Soccer Association, Connecticut Soccer League (CSL) and the Luso-American Soccer Association (LASA). The club played host to friendlies with Sporting Lisbon and other Portuguese clubs such as GD Chaves, SC Olhanense and CD Santa Clara, the visitors attracted by Lusitano Stadium, which the club insists is the only soccer-specific stadium in New England.

The clubhouse stays open late, and Pioneer coaches and players hang around the bar after practice. “If they like the club, they like what we do, I think they are going to give us 110 percent, not 100 percent,” Pioneers coach Federico Molinari said. “When you start feeling things for the club you care a lot more inside the field and this is what I want. Their commitment is unbelievable and they do it for free.”

Portuguese players long formed the basis of the Lusitano team. “All the teams we had, there were only seven or eight, or less, Portuguese players on the team,” Bernardo said. “We had Germans, Italians, great players from all [ethnicities]. Charlie McCully [who earned 11 caps for the U.S. National Team in the 1970s] played here. They didn’t care about your color, whatever you were.”

Among the players recognized by the Lusitano Alumni & Fans Committee, in their initial program in 1987, were William ‘Gil’ Bello, a member of the U.S. team that competed in the 1949 North American Football Championships (World Cup qualifiers) and Robert McIntyre, who started for a U.S. All-Star team that played to a 1-1 draw with Scotland’s national team at the Polo Grounds in New York City in 1939. Lusitano goalkeeper Tony Almeida and teammate Joseph Costa were named alternates on the 1948 U.S. Olympic team.

Lusitano competed in the shadow of another Portuguese club, Ponta Delgada, out of Fall River, that won the 1950 U.S. Open Cup and captured five U.S. Amateur Cup titles from 1946-53. Lusitano proved worthy opponents, reaching four Open Cup Quarterfinals from 1949-56. In 1949, Lusitano defeated Ponta Delgada for the New England title, then lost to New York SC in the Open Cup Quarterfinals.

In 1998, the club took a major step toward “Americanization” by joining the USISL. A local newspaper readers’ poll named the team the Western Mass Pioneers. In 1999, the Pioneers defeated the South Jersey Barons 2-1 in the USISL D3 Pro final before a crowd of about 6,000 at Lusitano Stadium. (Ludlow’s population was listed at 21,209 in 2000).

“You know what, it was the best thing we did,” Bernardo said of the name change. “Because this united the community more than anything else. People wouldn’t come to watch the soccer game when we were the Lusitanos. It was just Portuguese people watching the game. But now it’s totally different.”

From 2003-05 the New England Revolution made the stadium a base for their U.S. Open Cup games. They took a 2-1 win over the Rochester Rhinos on goals by Steve Ralston and Taylor Twellman before an estimated 4,000 fans in the 2003 Open Cup.

The next year (2004), the Rhinos eliminated the Revolution on penalty kicks at Lusitano Stadium and, in 2005, The Fire returned to take a 3-2 extra-time win over the Revolution before a full house on August 3, 2005. The suspenseful match included late red cards issued to the Fire’s Jesse Marsch (recently installed manager of Leeds United in England’s Premier League) and the Revolution’s Jay Heaps, who grew up in nearby Longmeadow, Massachusetts (and will return for the 2022 Open Cup as President and GM of Birmingham Legion FC).

Also in 2005, the Pioneers advanced to the third round of the U.S. Open Cup, falling to the Chicago Fire by a 3-1 score before a crowd of 4,000 at Lusitano Stadium. But the Pioneers gave the Fire a game with former Boston College star Neil Krause opening the scoring in the fifth minute.

Soccer generates profits, partly because of a concession area that includes alcohol sales and features the legendary bifana sandwich, a Portuguese specialty. But travel has proven costly, and the Pioneers chose to go amateur after losing on penalties to the Charlotte Eagles in the USISL D3 Pro final in 2005.

Lusitano Stadium underwent a makeover in 2013, a synthetic surface installed to accommodate an expanded youth program. Several grass fields are also maintained next to the stadium, behind Our Lady of Fatima church. “If you come to Lusitano Stadium now it is very similar to when you came 25 years ago to a Gremio Lusitano game, with the set-up and fan base,” Kolodziey said. “We’re trying to reach out to all fans now.

“What makes this special is definitely the history, most definitely the history,” Kolodziey added. “The players that played here, the fan base has been dedicated for a lot of years. When opposing teams come in here the atmosphere is pretty electric, the atmosphere is tight-knit. Teams like to play here on a Friday night, a couple thousand people – it’s a pretty neat thing for a small town.”

The Western Mass nickname, inspired by the area’s Pioneer Valley, is a nod to assimilation, but Portuguese influences remain strong here. Walls are adorned with a mosaic of the Trás-Os-Montes region of Northern Portugal and framed likenesses of Portuguese Ballon D’Or/World Players of the Year – Luis Figo and Cristiano Ronaldo. (The Figo picture has since been purchased by a fan).

The Boston Globe archives include dozens of Lusitano game stories, dating back to 1922. In 1940, after a game against Pawtucket, the club was ordered to pay a $75 fine, plus a $100 “soccer peace bond” for what was described as a “riot” and “fracas,” leading to a one-year suspension for Pawtucket’s Harry Burness.

“The fans love their soccer,” said Fred Pereira, former player and the Town of Ludlow’s Tax Collector. “Fans are very close to the field so it’s very easy to get excited. We do have some fans who are passionate. It’s all part of the tradition – keep it under control but have some passion.”

Pereira, who set a Ludlow High School record with 50 goals in a season, might have been the first to follow a path from this club to the Ivy League to pro soccer (the latest would be New England Revolution midfielder Tommy McNamara). “I was born in Portugal and came here when I was 12,” said Pereira, 64, who played at Brown University, then in the NASL and for the U.S. men’s national team. “Fortunately, it was a very good soccer town and that made it easier for me to make friends. Ludlow is a good town to come to if you’re a soccer player.”

There’s a tradition that connects people in Ludlow to their roots overseas and the game they love. It lives in Lusitano Stadium and the boys who line up there – call them the Lusitanos or the Pioneers, it doesn’t matter – it’s all the same in Ludlow.