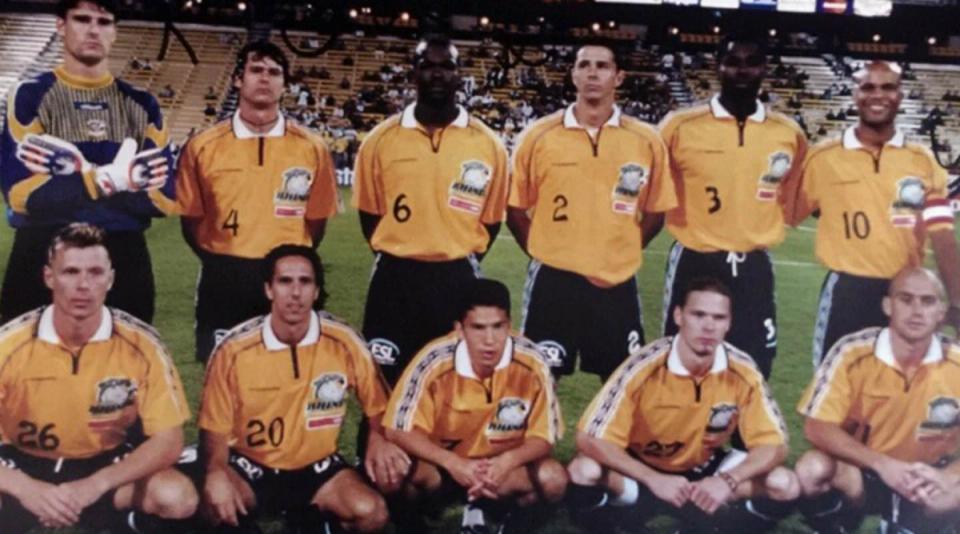

Open Cup REWIND: ‘99 Rhinos - If You Can’t Join ‘em, Beat ‘em!

Still the gold standard for underdogs in the Open Cup’s Modern Era, take a look back at the 1999-champion Raging Rhinos of Rochester, New York.

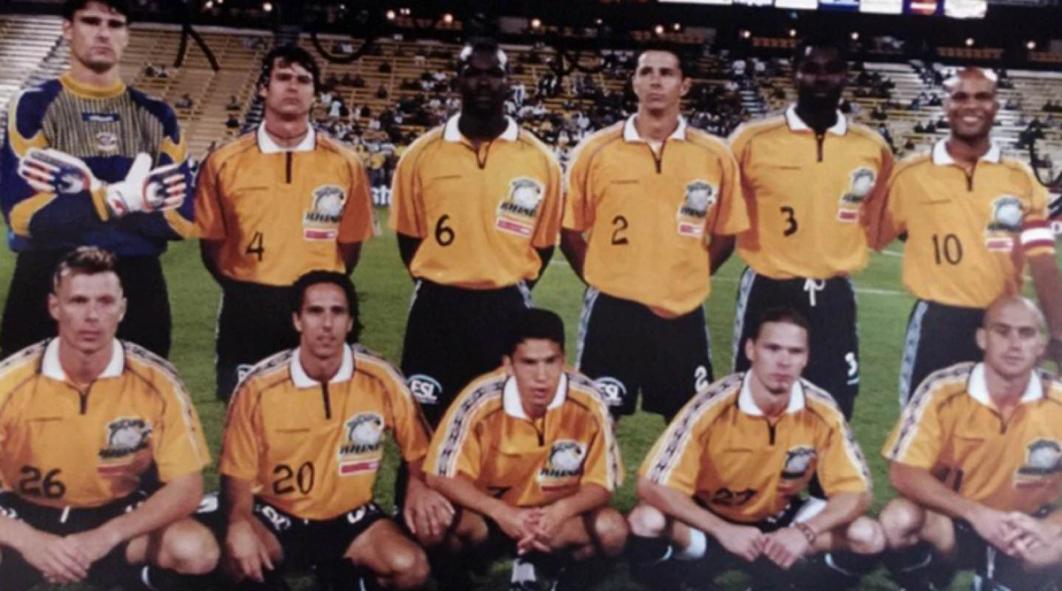

The 21st century hadn’t even dawned the last time a team that wasn’t in Major League Soccer won the Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup. But back in 1999 the Rochester Raging Rhinos carved out a place in history with attitude, ego and a big chip on their shoulder.

“Swagger is a good way to put what we had,” coach Pat Ercoli told usopencup.com. “We were borderline out of control with it!” agreed Rhinos goalkeeper Pat Onstad

The Rochester Rhinos began life in 1996, the same year MLS was founded as the new and gleaming peak of the American soccer pyramid. With a squad of seasoned professionals, most of whom played upwards of 80 games a year – both outdoor and indoor – the second-division Rhinos seemed like prime contenders for a place in the fledgling top-flight. The city had soccer in its veins and a rich history going back even before the Lancers of the old North American soccer League (NASL). Hordes of fans, often hovering around the 15,000-mark, steamed through the turnstiles every weekend at the tiny Frontier Field.

“It was like, ‘look what we’re doing here!’” said Scott Schweitzer, Rochester defender from 1998 to 2003. “We thought we should be in MLS. We’re sold out every week. We had more fans coming out than a lot of the MLS teams did. A lot more.”

But economic factors, calculators, accountants and spreadsheets conspired to keep the Rhinos and their legions of fans from the big-time. When the 1999 Open Cup rolled around, they had a new and potent slogan. It was printed on stickers, t-shirts and banners, and chanted in the stands: If you can’t join ‘em, beat ‘em!

“It was our rallying cry,” said Onstad, the Canadian legend who went on to a long and distinguished career in MLS. “We were a bunch of misfits. We worked harder for each other than any team I’ve ever played on and everyone had something to prove. A lot of the guys felt like they should be in MLS, but that call never came.”

Schweitzer was one of those swaggering misfits, perhaps chief among them. He was 11 the first time he kicked a soccer ball around inner city New Jersey and he remembers being tagged a “commie” on the schoolyard for his quick interest in the game. “I didn’t care,” he recalled with a shrug. “I knew the first day I played that I was going to be a pro. I didn’t know what that meant, but I knew it was true.”

The Rhinos went on a run for the ages in the 1999 Open Cup, slaying four straight MLS sides. “We always thought we had a chance no matter who we were playing,” said Schweitzer, who credits soccer for seeing him through a rough childhood. And he speaks of the city of Rochester with the kind of affection reserved for a family member. “I understood the city and the city understood me,” he said, remembering living downtown in an old brick building and seeing his own face, 50 feet up and huge over the highway, plastered on a Go-Rhinos billboard.

“We were big on being boisterous,” said Schweitzer, who was a two-time All American at NC State and later coached the Carolina RailHawks (now North Carolina FC of the USL Championship). “Maybe cocky is a better word. But we wanted to show people something, show them what we could do and what soccer in Rochester was all about.”

The Rhinos played their first two games against MLS opposition at their Frontier Field, an improvised home designed for baseball. “OK, so the field was 69 yards wide and maybe 110 long – so you do that math,” said Ercoli.

Onstad remembers the pitch too, with an attention to detail befitting a goalkeeper. “The dirt infield ran right through the middle of the pitch. And somehow, the field always seemed to be slanted! I don’t know how, but it did!”

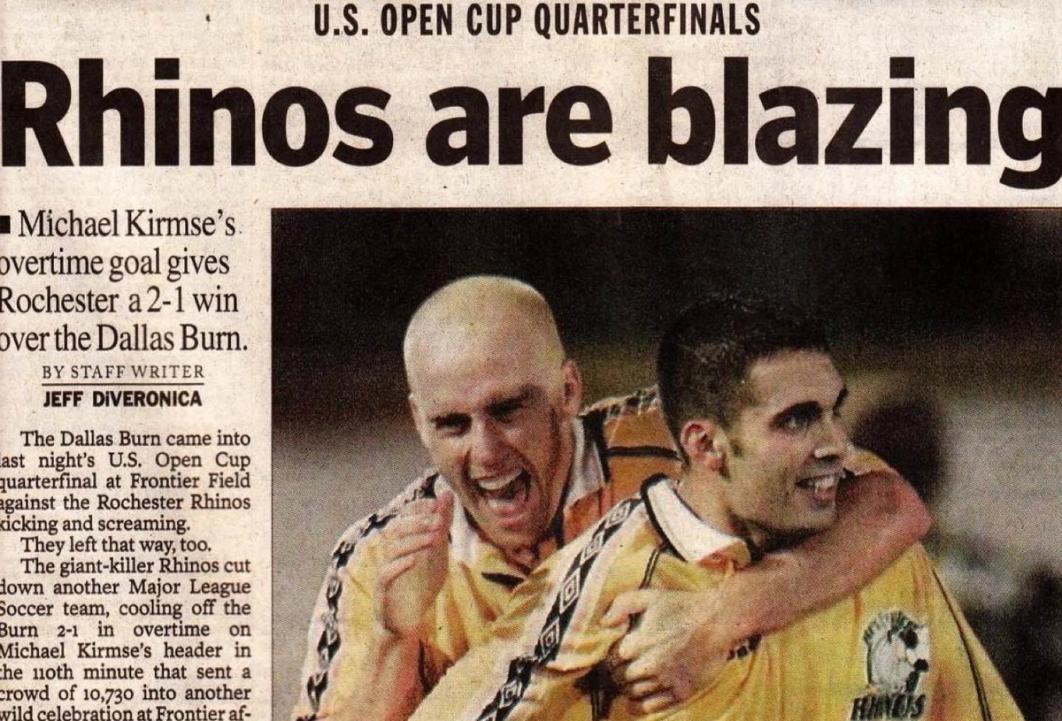

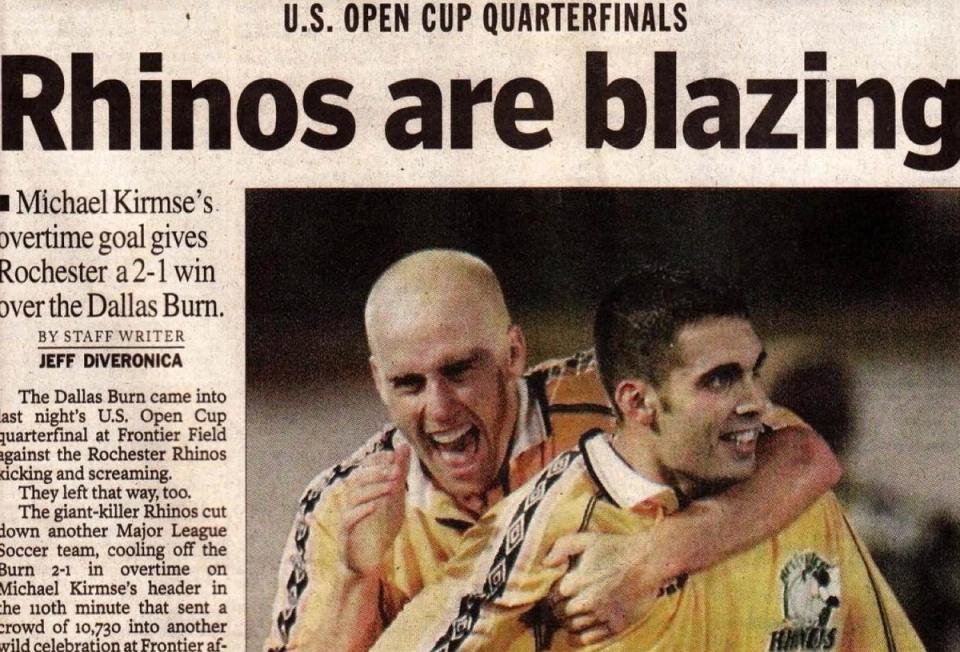

The Rhinos beat Bob Bradley’s Chicago Fire at home with what can politely be described a “physical” approach. Rochester committed nearly 50 fouls in the game and did a similar number in their next: A 2-1 golden-goal win over 1997 Open Cup champs Dallas Burn (now FC Dallas). After the game, Dallas’ star striker Jason Kreis wasn’t interested in playing diplomat when he said Rochester would “get their butts beat on a real field.”

The trash talk and the sour grapes of their beaten opponents didn’t bother Ercoli and co. Not one bit. In fact, it was just the kind of motivation the jilted Rhinos needed to grow that chip on their shoulder. Their Semifinal was on the road, on one of those real pitches, against a Columbus Crew side led by U.S. National Team stars like Brian McBride and Thomas Dooley. But, luckily for the Rhinos, the heavens intervened.

“We played down in Virginia on the edge of a hurricane,” said Onstad, recalling the first game away from their wild fans and compact home. “It was like no wind I’d ever seen,” added Ercoli, who instructed captain Tommy Tanner to go against it in the first half. “He looked at me like I was crazy! We’re talking 50 mile-per-hour winds here!”

The first half ended goalless and “we celebrated like we just won the Cup!” said Onstad. But in the second half, the game broke open. Big striker Darren Tilley leveled for the Rhinos after a sensational free-kick by Poland international Robert Warzycha put Columbus ahead. When the Crew went up again with 12 minutes to go, the Rhinos’ charge looked over. But two goals in the last four minutes, with a little help from the wind at their backs, sent the men from Rochester through to the Final.

“We were the kind of team that always found a way to win,” said Ercoli, who also guided the side to the Final in 1996 and remains president of the Rochester Rhinos organization. “And in the end, the Crew petered out while we rode the wind, and a little bit of luck.”

That game in the blustery gales, on the ragged edges of a tropical storm, was the moment when a reality hit home in the team. “I started to have this feeling,” said Onstad. “Ok, we’re going to do this.” Ercoli’s gut told him the same: “We went to Columbus, Ohio for the Final with the attitude of: This is destiny.”

The Final was at the brand-new Crew Stadium against the Colorado Rapids. And with their own team gone, the Columbus fans adopted the traveling underdogs. They joined the chorus led by busloads of traveling fans that rolled in from Rochester. “They were there to greet us in Ohio when we got off the bus,” Schweitzer recalled.

“They had their banners – if you can’t join ‘em, beat ‘em and all that. You didn’t want to let these people down.”

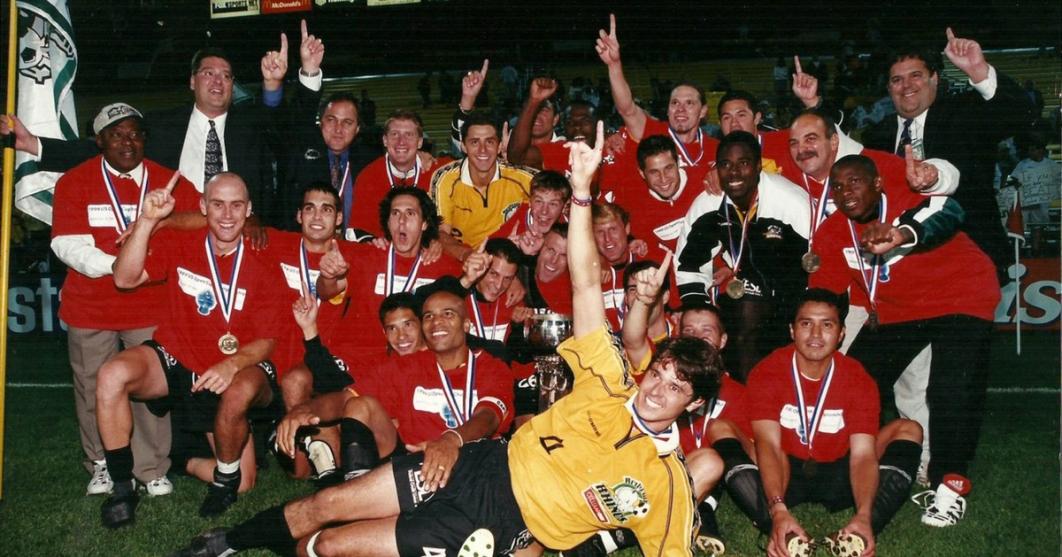

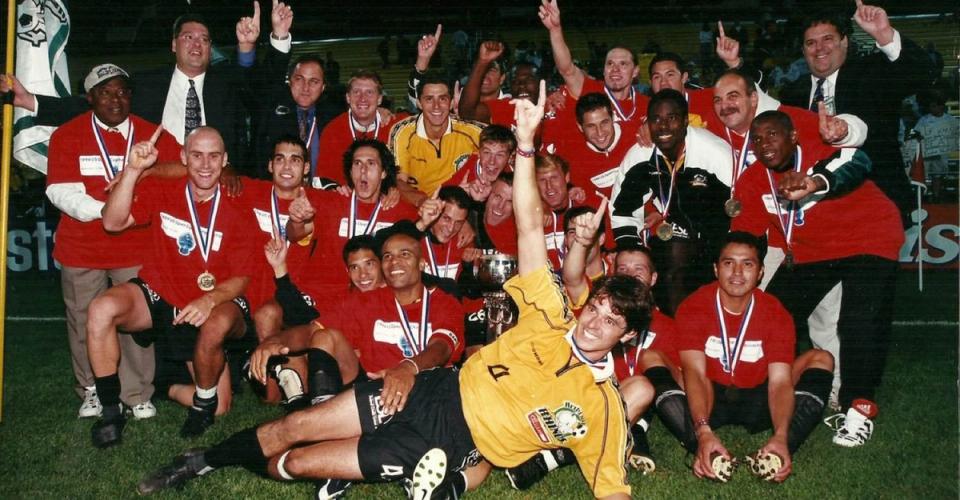

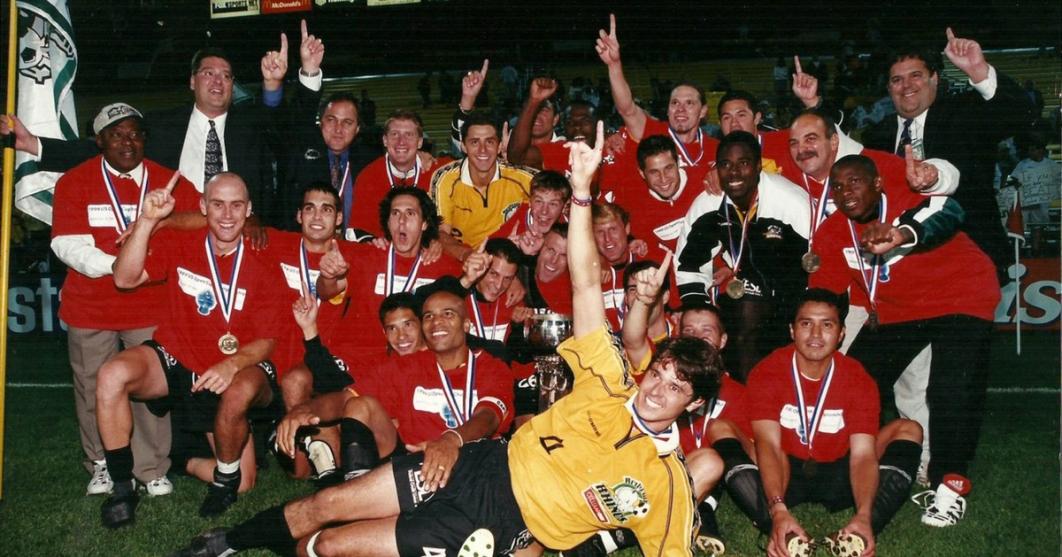

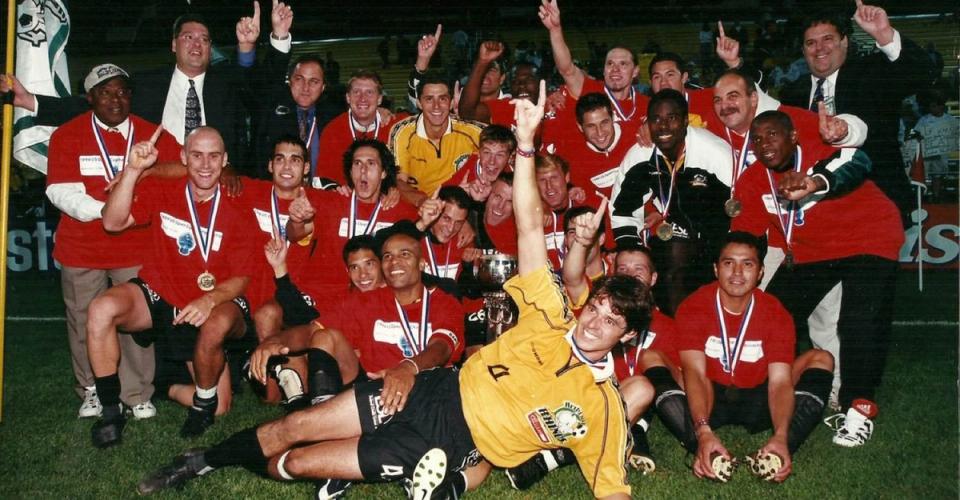

And they didn’t. A first goal from “Deadly” Doug Miller and a late one from Yari Allnutt saw the unfancied Rhinos win out 2-0. “I don’t remember having to do that much work on the day either,” said Onstad. “What I remember most is the pride at the end, being there with this great team of crazy guys, holding the trophy.”

“Maybe someday another non-MLS team will do it again, but it’s not easy,” said Ercoli. “It was an amazing thing,” added Schweitzer. But the last word went to Onstad, who fought his MLS coaches later in his career when they wanted to rest him for Open Cup games. “I’d insist they put me in for the Cup.” said the man who went on to win three MLS titles. Twice he was named MLS’ goalkeeper of the year, but he never got his hands on the Open Cup again. “It always mattered to me.”