Whatever Happened to Former USMNT Captain Mike Windischmann?

ussoccer.com Catches Up With the 1990 USMNT World Cup Captain

Mike Windischmann knows all about the thrill of victory the and the agony of defeat, particularly when it comes to World Cup qualifying.

He lived through a pair of results that spanned the opposite ends of the emotional spectrum.

As a 19-year-old on May 31, 1985, the center back tasted bitter defeat with his USMNT teammates, a crushing 1-0 home loss to Costa Rica that eliminated the Americans from contention for the 1986 World Cup.

"Everybody in the locker room, guys like Ricky Davis, were sitting there with their hands in their face because they probably realized that was it for them," Windischmann said. "I was very disappointed, but I was hoping to stay with the national team for the next World Cup."

As the only starter from that 1985 squad in Port of Spain, Trinidad on Nov. 19, 1989, Windischmann celebrated with his teammates as the USA recorded a 1-0 win to end 40 years in the World Cup desert, booking a spot at Italia '90.

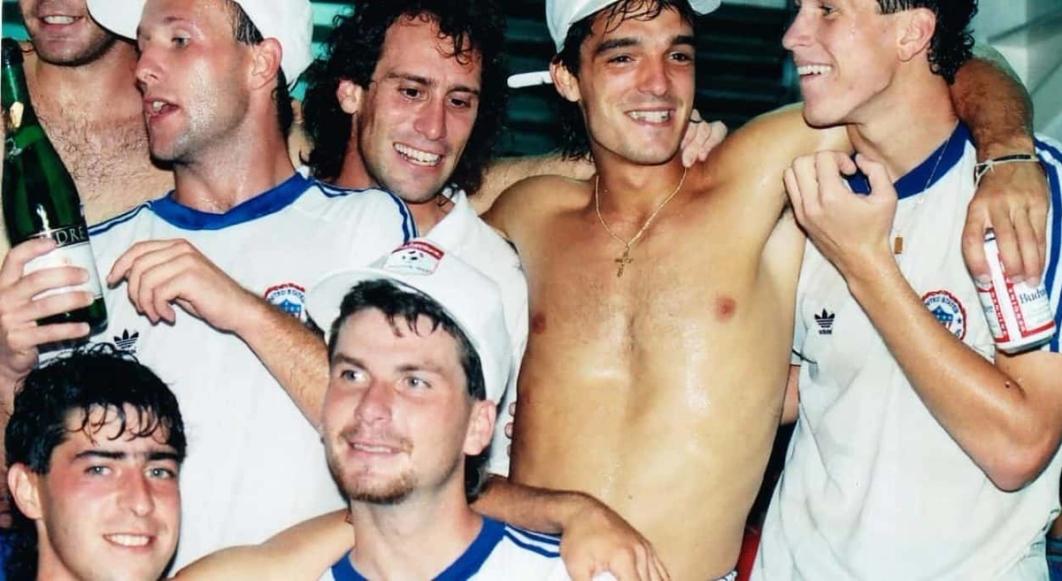

"It was unbelievable," he said. "You either put your hands to your head or you fell to the ground. Oh, my goodness, we're going to the World Cup! Just hugging everybody. Going into the locker room they [Trinidad fans] were throwing beer on us. We just looked up and said, 'Yeah, we're going to the World Cup and you're not!' That was such an unbelievable feeling that hadn’t happened in 40 years.”

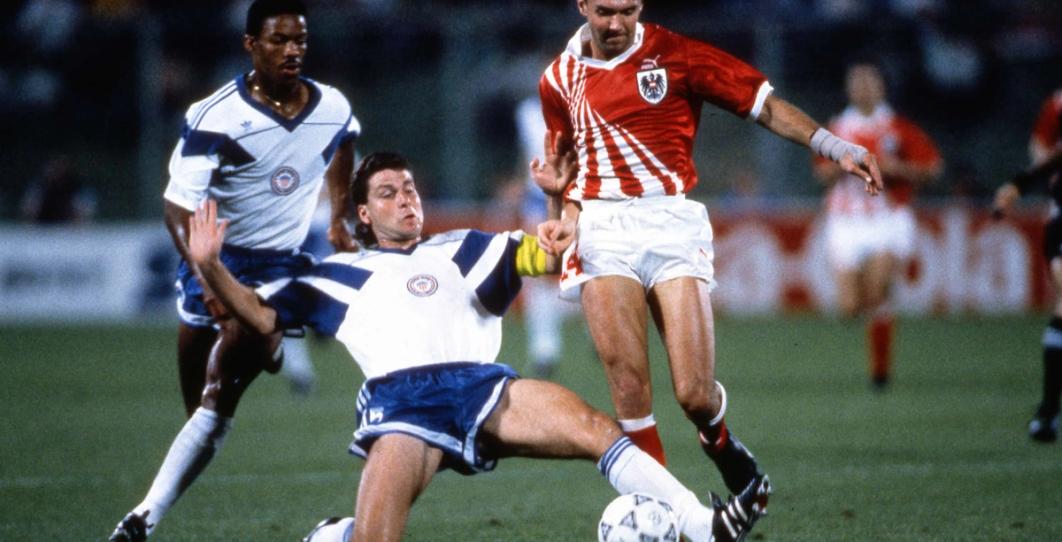

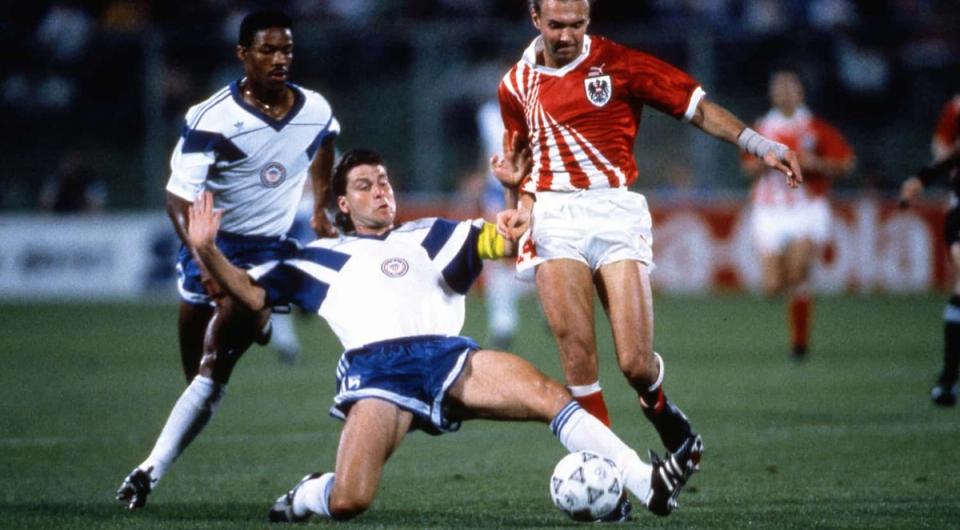

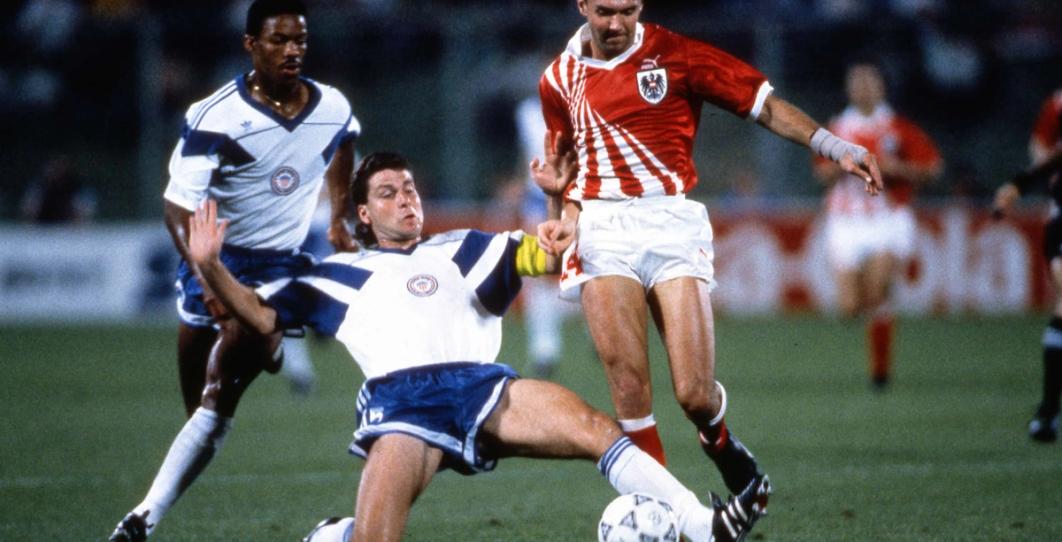

Windischmann (right below), a 2004 inductee into the National Soccer Hall of Fame, was a natural to captain that World Cup team.

“He was technically talented and tactically extremely aware,” former USMNT head coach Bob Gansler said. “You could tell he was a student of the game. He just had those leadership qualities. He did it by example and did it in a quiet, confident manner. He had a calming influence on the field. I don't think his pulse ever went awfully high. He was confident to say, ‘I can handle this’ without being arrogant. He had those qualities that made sense to put him out front."

That wasn't lost on his teammates.

"He was kind of different from everybody else," midfielder Tab Ramos said. "Even though we were all young, he was mature. He was calm. He had this aura about him like he was the older guy. He was maybe six months older than anyone else. He was a great captain.”

Just how much did Windischmann love performing for the national side?

“You probably could have given me a dollar a year and I still would have played,” he said.

While growing up in Queens, N.Y., Windischmann performed for B.W. Gottschee, Queens United and S.C. Gjoa. His family lived in the Ridgewood section, home of the Metropolitan Oval, a great magnet for soccer - youth, amateur, semi-pro and pro and international matches.

The Oval was a great classroom. Before it was replaced by artificial turf, the venue was more known for its dirt and rocks.

"It's crazy. It’s an advantage," Windischmann said. "People coming from Westchester and out of state, they're not used to dirt. You come there and its rocks and dirt and a railing going around the whole touchline. And the dust flying up and trains flying by [nearby] and the smoke coming to the field. They were probably a little intimidated."

Which gave Windy an appreciation of other fields that were not necessarily in pristine condition.

“It helped my touch; it helped my skill. Playing over there helped those things," he said. "It's funny. When I was with the national team, I remember some of the California guys when we saw the field, it wasn't perfect grass. 'Ah, this field is horrible.' I'm like, 'This is perfect, man. I'm coming from dirt and rocks.’ "

He lived, ate and breathed soccer. As a New York Cosmos fan, Windischmann was at JFK Airport in 1977 to greet legendary German defender Franz Beckenbauer, who signed with the North American Soccer League club.

He held a sign that read: “Herzlich Wilkommen”, (A warm welcome).

"Two months later I opened up the mailbox and there's an autographed picture that Beckenbauer sent me," Windischmann said. "It had my address on the card. I still have the envelope and the card he sent me. I bet not many people have that.”

Despite playing for Eastern New York Youth Association and Region I teams, Windischmann was not recruited heavily out of Thomas Edison High School. He discovered Adelphi University in nearby Garden City, N.Y. and liked what he saw of coach Bob Montgomery (most recently the New York Red Bulls Academy director).

"I was appreciative that Bob Montgomery recruited me," he said. "Adelphi was a good Division I program. When the national team started calling guys to try out, teams like N.C. State and some of the bigger colleges weren't releasing their players to miss a little bit of preseason. So, I am thankful to Adelphi that they allowed me.”

Windischmann learned that he earned a spot on the U.S. qualifying roster for Mexico '86 in a unique way. At 8:30 one morning, the pay phone rang in the hall of his dorm at Adelphi.

"Hey, Windy, you got a phone call," someone yelled from down the hall.

The call came from Region I director George Donnelly, who coached Windischmann at Gjoa.

"I was amazed," he said. "Being that young and playing with Ricky Davis and all those guys was unbelievable. It was my dream."

It eventually became a nightmare. The semifinal round had four U.S. matches -- home-and-home series with Costa Rica and Trinidad & Tobago during a 17-day period. With no first division league, the U.S. was comprised of college players and others from the Major Indoor Soccer League. The Americans entered the final match in Torrance, Calif. against Costa Rica at 2-0-1 and needed a tie to reach the final round.

"We were confident. We couldn't have played a better game except for not scoring," Windischmann said. "Basically, one mistake. The guys played the best that we could, but we couldn't get that tying goal."

Coupled with the fact the North American Soccer League went belly-up after 1984, it was considered the lowest point in modern American soccer history.

Windischmann wound up playing for the Brooklyn Italians, one of the best amateur/semi-pro clubs in the New York area, the Los Angeles Lazers in the Major Arena Soccer League (1988-89) and Albany Capitals (1989-90) in the American Soccer League.

He captained the USA at the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul and scored a goal in the 1-1 deadlock with Argentina.

In January 1989, he was among several members of the USMNT represented their country at the first FIFA Futsal World Championship in the Netherlands. To the surprise of many, the Americans finished third. Windischmann tallied the game-winning goal in a 3-2 win against Belgium in the Third-Place Match.

"Tab Ramos said it. The 1989 team was the most fun we've ever had playing soccer together," he said. “We just kept on winning. Just incredible to finish that high."

(In 1992, Windischmann helped the USA take second place in the same tournament).

It was a perfect warm-up for a team that would face its greatest challenge – an eight-game round-robin against Costa Rica, Trinidad & Tobago, Guatemala and El Salvador. The Ticos clinched their first World Cup appearance. The Americans and Soca Warriors wound up battling for the final berth.

The USA entered the final day of qualification in Trinidad on Nov. 19 needing a victory to advance. Beyond just qualifying for Italia '90, the team shouldered a huge burden for the future of U.S. Soccer. In 1988, the USA was named to host the 1994 World Cup. It would have been embarrassing and a grand opportunity missed had the team failed to qualify.

"Before the game I said that if we lose, we're probably going to have get regular jobs or do different things because there aren't going to be that many international games," Windischmann said. "The national team is probably going to take a hiatus for a year or two before '94. You're fighting for the country and you want to continue to play. It would have been a nightmare. We accepted the pressure."

The USMNT survived in Port of Spain, using Paul Caligiuri’s lone goal in earning a 1-0 victory against the Soca Warriors to punch it ticket to Italia ’90. The result is one of the most seminal moments in U.S. Soccer history.

The Americans brought a young team to Italy (average age was 23). Players were recent college graduates without much professional experience. The USA's first World Cup match in four decades was a disaster, a 5-1 loss to Czechoslovakia.

"Going there we didn't look at ourselves as college guys," Windischmann said. "We had a tough group. Czechoslovakia and Italy went far in the World Cup. We didn't play well the first game and went down a man, which didn't help. When we came down the stairs the Czechoslovakian team was strong. They were all 6-2, 6-3. We bounced back that second game. It could have been a disaster if we didn't get our act together."

That second game was a 1-0 loss to Italy, as the USMNT turned the hosts’ supporters against them. Had the Americans have any luck, they could have walked out with a draw.

“They felt we were going to lose 10-0 after the first game. It was nice to hear the Italian fans cheering us,” Windischmann said. “The Italian players came into the locker room after the game and congratulated us."

In its final group game, the U.S. suffered a 2-1 loss to Austria in an ill-tempered affair as the Americans enjoyed a man advantage for almost an hour.

The veteran Windischmann was so important to the maturing side that he appeared in every match the USMNT played between July 1988 and November 1990. His 36-consecutive appearances in the time is a record which still stands today and is likely never to be broken.

As integral as “Windy” had been to the side the previous two years, ultimately his consecutive game run ended the same day as his senior international career when he suffered a partially torn anterior cruciate ligament in a 0-0 draw with the Soviet Union.

The site was Queen’s Park Oval in Port of Spain, Trinidad, just over a mile away from Hasely Crawford Stadium where the USMNT triumphed over the Soca Warriors to go to the World Cup one year and two days earlier. Windischmann still played for the USA at the 1992 FIFA Futsal World Cup, but the injury in Trinidad ended any chance of pushing for a roster spot in 1994.

"That was a disappointment," he said. “I was hoping it was cartilage, but I knew it wasn't cartilage. It didn’t respond the way I wanted to. Even then during the futsal tournament, the knee wasn't responding. You just have to accept what happened. It was very disappointing. God wanted me to go a different way."

That way was coaching teaching. Windy coached at Forest Hills High School, at the Berkeley Carroll School, Met Oval and with the Super Y League. He teaches at the Susan B. Anthony Academy in Queens and deals with at risk students in the Teen Center in New York City.

His son, Michael Jr., 16, worked his way onto the Floral Park Memorial High School team as a left back, not unlike his father’s early days. He also competes for Valley Stream (Long Island Junior Soccer League's Premier Division).

"He is trying to pave his way," his father said.

Though his career ended well before he had expected and he missed out playing first division soccer, Windischmann still counted his blessings.

"My career was caught in between two leagues," he said. "When the NASL folded and by the time, MLS started, I was not playing anymore. What came for me was the national team. I appreciated it."